The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) left a legacy of daring and innovation that has influenced American military and intelligence thinking since World War II.

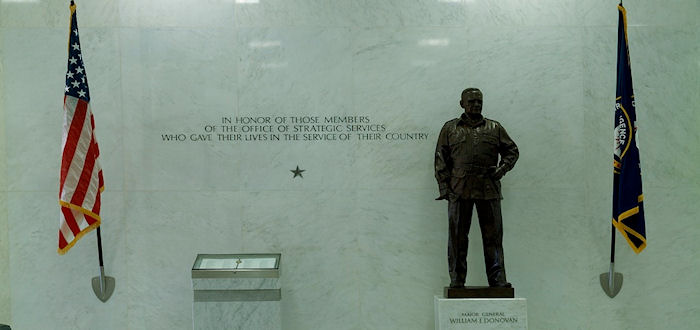

OSS owed its successes to many factors, but most of all to the foresight and drive of William J. Donovan, who built and held together the office's divergent missions and personalities.

Given the toughness of OSS's adversaries and the difficulty of the tasks assigned to the office, Donovan and his lieutenants could take pride in what they achieved. Ironically, by the end of the war, he had done his job so well that his presence was no longer essential to carry American intelligence into a new peacetime era. When the White House wanted to retire him in 1945, it also took care to save valuable components of the office that he had created. Today's Central Intelligence Agency derives a significant institutional and spiritual legacy from OSS. In some cases this legacy descended directly; key personnel, files, funds, procedures, and contacts assembled by OSS found their way into the CIA more or less intact. In other cases the legacy is less tangible—but no less real.

Before World War II, the US Government traditionally left intelligence to the principal executors of American foreign policy, the Department of State and the armed services. Attachés and diplomats collected the bulk of America's foreign intelligence, mostly in the course of official business but occasionally in clandestine meetings with secret contacts. In Washington, desk officers scrutinized their reports in the regional bureaus and the military intelligence services (the Office of Naval Intelligence [ONI] and the War Department's Military Intelligence Division, better known as the G-2).

As another European war loomed in the late 1930s, fears of fascist and Communist "Fifth Columns" in America prompted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to ask for greater coordination by the departmental intelligence arms. When little seemed to happen in response to his wish, he tried again in the spring of 1941, expressing his desire to make the traditional intelligence services take a strategic approach to the nation's challenges—and to cooperate so that he did not have to arbitrate their squabbles. A few weeks later, Roosevelt in frustration resorted to a characteristic stratagem. With some subtle prompting from a pair of British officials—Admiral John H. Godfrey and William Stephenson (later Sir William)—FDR created a new organization to duplicate some of the functions of the existing agencies. The President on 11 July 1941 appointed William J. Donovan of New York to sort the mess as the Coordinator of Information (COI), the head of a new, civilian office attached to the White House.

The office of the Coordinator of Information constituted the nation's first peacetime, nondepartmental intelligence organization. COI, said historian Thomas F. Troy, was "a novel attempt in American history to organize research, intelligence, propaganda, subversion, and commando operations as a unified and essential feature of modern warfare; a 'Fourth Arm' of the military services." The office grew quickly in the autumn before Pearl Harbor, with Donovan cheerfully accumulating various offices and staffs orphaned in their home departments.

America's entry into the war in December 1941 provoked new thinking about the place and role of COI. Donovan and his new office—with its $10 million budget, 600 staffers, and its charismatic director—had provoked hostility from the FBI, the G-2, and various war agencies. The new Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) initially shared this distrust, regarding Donovan, a civilian, as an interloper—but one they might be able to control and utilize if COI could be placed under JCS control. Surprisingly, Donovan himself, by now, was inclined to agree. Working with the Secretary of the JCS, Brig. Gen. Walter B. Smith, Donovan devised a plan to bring COI under the JCS in a way that would preserve the office's autonomy while winning it access to military support and resources.

President Roosevelt endorsed the idea of moving COI to the Joint Chiefs. The President, however, wanted to keep COI's Foreign Information Service (which conducted radio broadcasting) out of military hands. Thus he split the "black" and "white" propaganda missions, giving FIS the officially attributable side of the business—and half of COI's permanent staff—and sent it to the new Office of War Information. The remainder of COI then became the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) on 13 June 1942. The change of name to OSS marked the loss of the "white" propaganda mission, but it also fulfilled Donovan's wish for a title that reflected his sense of the "strategic" importance of intelligence and clandestine operations in modern war.

A month later, OSS's institutional rivals delivered another blow to Donovan's aspirations for the new outfit. The Department of State and the armed services arranged a Presidential decree that effectively banned OSS and several other agencies from acquiring and decoding the war's most important intelligence source: intercepted Axis communications. Donovan protested, but his complaints fell on deaf ears. The result was that OSS had no access to intercepts on Japan (codenamed MAGIC) and could read only certain types of German intercepts (called ULTRA by the Allies). Other edicts also limited OSS's scope and effectiveness. The FBI, G-2 and ONI, for instance, stood together to protect their monopoly on domestic counterintelligence work. OSS eventually developed a capable counterintelligence apparatus of its own overseas—the X-2 Branch—but it had no authority to operate in the Western Hemisphere, which was reserved for the FBI and Nelson Rockefeller's office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs.

OSS expanded in 1942 into full-fledged operations abroad. Donovan sent units to every theater of war that would have them. His can-do approach had already impressed the State Department, which in 1941 had desperately needed men to serve as intelligence officers in French North Africa. Donovan's COI sent a dozen officers to work as "vice consuls" in several North African ports, where they established networks and acquired information to guide the Allied landings (Operation TORCH) in November 1942. The success of TORCH won OSS much needed praise and supporters in Washington. Unfortunately, General Douglas MacArthur in the South Pacific and Admiral Chester Nimitz in the Central Pacific saw little use for OSS, and the office was thus kept from contributing to the main American campaigns against Imperial Japan. Nonetheless, Donovan forged ahead and hoped for the best. Utilizing military cover for the most part, but with some officers under diplomatic and non-official cover, OSS began to build a world-wide clandestine capability.

This worldwide reach benefited from close OSS contacts with British intelligence services. The British had much to teach their American pupils when COI opened its London office in November 1941. Both sides gained from the partnership. OSS needed information, training, and experience, all of which the British organizations could provide. The British good-naturedly envied the relative wealth of resources seemingly at the command of OSS and other American agencies and hoped to share in that bounty to expand their own operations against the Axis. Despite a mutual desire to cooperate, however, relative harmony between OSS and its British counterparts took time to achieve.

The slow maturing of inter-Allied cooperation had several causes. British intelligence services had their own operations and plans to protect and feared that working too closely with the inexperienced Americans would jeopardize the safety of their operatives in occupied Europe. This British caution kept the Americans in the awkward status of junior partners for much of the war, particularly during the planning for covert action in support of the D-Day landings in Normandy in 1944. For their part, OSS officers worried about making their new agency dependent on even a friendly foreign intelligence service. Conflicting policy goals occasionally hampered liaison with the British services in Asia. American diplomacy quietly frowned on British imperialism, and some OSS officers informally opposed British moves they viewed as efforts to expand the Empire. Despite these obstacles, however, the liaison relationship gradually grew closer as shared sacrifices and common goals forced officers in the field and in their respective headquarters to resolve their differences.

At its peak in late 1944, OSS employed almost 13,000 men and women. In relative terms, it was a little smaller than a US Army infantry division or a war agency like the Office of Price Administration, which governed prices for many commodities and products in the civilian economy. General Donovan employed thousands of officers and enlisted men seconded from the armed services, and he also found military slots for many of the people who came to OSS as civilians. US Army (and Army Air Forces) personnel comprised about two-thirds of its strength, with civilians from all walks of life making up another quarter; the remainder were from the Navy, Marines, or Coast Guard. About 7,500 OSS employees served overseas, and about 4,500 were women (with 900 of them serving in overseas postings). In Fiscal Year 1945, the office spent $43 million, bringing its total spending over its four-year life to around $135 million (almost $1.1 billion in today's dollars).

Research & Analysis

American academics and experts in the Office of Strategic Services virtually invented the discipline of non-departmental strategic intelligence analysis—one of America's few unique contributions to the craft of intelligence. Inspired by General Donovan's vision of a service that could collate data from open sources and all departments of the government, analysts in OSS's Research and Analysis Branch (R&A) comprised a formidable intelligence resource.

R&A made one of its biggest contributions in its support to the Allied bombing campaign in Europe. Analyses by the Enemy Objectives Unit (EOU), a team of R&A economists posted to the US Embassy in London, sent Allied bombers toward German fighter aircraft factories in 1943 and early 1944. After the Luftwaffe's interceptor force was weakened, Allied bombers could strike German oil production, which EOU identified as the choke-point in the Nazi war effort. The idea was not original with OSS, but R&A's well-documented support gave it credibility and helped convince Allied commanders to try it. When American bombers began hitting synthetic fuel plants, ULTRA intercepts quickly confirmed that the strikes had nearly panicked the German high command. Although the fighting in Normandy that summer delayed the full force of the "oil offensive," in the autumn of 1944 Allied bombers returned to the synthetic fuel plants. The resulting scarcity of aviation fuel all but grounded Hitler's Luftwaffe and, by the end of the year, diesel and gasoline production had also plummeted, immobilizing thousands of German tanks and trucks.

Special Operations

The Special Operations Branch (SO) of OSS ran guerrilla campaigns in Europe and Asia. As with many other facets of OSS's work, the organization and doctrine of the Branch was guided by British experiences in the growing field of "psychological warfare." British strategists in the year between the fall of France in 1940 and Germany's invasion of the USSR in 1941 had wondered how Britain—which then lacked the strength to force a landing on the European continent—could weaken the Reich and ultimately defeat Hitler. London chose a three-part strategy to utilize the only means at hand: naval blockade, sustained aerial bombing, and "subversion" of Nazi rule in the occupied nations. A civilian body, the Special Operations Executive (SOE), took command of the latter mission and began planning to "set Europe ablaze." This emphasis on guerrilla warfare and sabotage fit with William Donovan's vision of an offensive in depth, in which saboteurs, guerrillas, commandos, and agents behind enemy lines would support the army's advance. OSS thus seemed the natural point of contact and cooperation with SOE in combined planning and operations when the Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff decided in 1942 that America would join Britain in the business of "subversion."

The Special Operations Branch served as SOE's American partner. Together, SO and SOE created the famous "Jedburgh" teams parachuted into France in the summer of 1944 to support the Normandy landings. Jedburghs joined the French Resistance against the German occupiers. There were 93 three-man teams in all, each of them with two officers and an enlisted radio operator. Typically an OSS man would serve with a British officer and a radioman from the Free French forces loyal to General Charles de Gaulle. Trained as commandos at SOE's Milton Hall in the English countryside, they were a colorful and capable lot that included adventurers and soldiers of fortune, as well as author Stewart Alsop and future Director of Central Intelligence William Colby. Officers trained alongside enlisted men in informal comraderie because, once inside France, rank would have to be secondary to courage and ability. After landing (hopefully into the arms of the Resistance) the teams coordinated airdrops of arms and supplies, guided the partisans on hit-and-run attacks and sabotage, and did their best to assist the advancing Allied armies.

Secret Intelligence

William J. Donovan in 1941 had not intended his new intelligence service to become a "spy" agency, running espionage operations in foreign capitals. He wanted COI to support military operations in the field by providing research, propaganda, and commando support, but he quickly became convinced of the value of clandestine human reporting. In 1942 OSS established the Secret Intelligence Branch (SI) to open field stations, train case officers, run agent operations, and process reports in Washington. Headed from 1943 on by international executive and lawyer Whitney H. Shepardson, SI by the end of the war had become a full-fledged foreign intelligence service, with stations in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, excellent liaison contacts with foreign services, and a growing body of operational doctrine.

In November 1942, the most famous SI station chief, Allen W. Dulles, set up shop on "Hitler's doorstep" in the American legation in Bern, Switzerland. He found there a complicated and ever-shifting scene. Dulles quickly adopted a remnant of the fine prewar French military intelligence service, which gratefully provided him reports on German deployments in France that were prized by Allied invasion planners. He also found that Allied agents sent into Nazi Germany had scant hope of eluding the Gestapo, but that travel between the Reich and neutral Switzerland was free enough to bring a variety of Germans to him. Dulles established wide contacts with German émigrés, resistance figures, and anti-Nazi intelligence officers (who linked him, through Hans Bernd Gisevius, to the tiny but daring opposition to Hitler in Germany itself). Although Washington barred Dulles from making firm commitments to the plotters of the 20 July 1944 attempt to assassinate Hitler, the conspirators nonetheless gave him reports on developments in Germany, including sketchy but accurate warnings of plans for Hitler's V-1 and V-2 missiles. In addition, Dulles was contacted by a German Foreign Ministry official, Fritz Kolbe, who volunteered to report from Berlin. Kolbe's periodic packets illuminated German foreign policy and military matters, and helped the British spot the German spy "Cicero" working in the household of the British ambassador to Turkey.

Secret Intelligence Branch operations by 1945 had extended beyond the running of operations in foreign capitals to encompass the actual penetration of Nazi Germany. Donovan wanted to replicate the successes that the SI mission in Algiers had had in running the "Penny-Farthing" network in Southern France, but Germany, with no organized Resistance, was a much tougher objective. SI's mission in London, led by William J. Casey, found a solution by adopting the methods of a successful OSS Morale Operations Branch project in Italy. Casey's unit—knowing that no Americans could survive in Hitler's Germany—learned how to find "volunteer" agents among the thousands of Axis prisoners-of-war in England. Casey's London SI trained the agents, provided them with meticulously prepared clothing, documentation, and equipment, and dropped nearly 200 of them into the Third Reich to gather intelligence in the last months of the war. Agent teams established themselves in Bremen, Munich, Mainz, Dusseldorf, Essen, Stuttgart, and Vienna—and even in Berlin. They paid a high price in casualties—36 were killed, captured, or missing at war's end—but the data they collected on industrial and military targets significantly aided the final Allied air and ground assaults on Germany.

Weapons & Spy Gear

OSS activities created a steady demand for devices and documents that could be used to trick, attack, or demoralize the enemy. Finding few agencies or corporations willing to undertake this sort of low-volume, highly specialized work, General Donovan enthusiastically promoted an in-house capability to fabricate the tools that OSS needed for its clandestine missions. By the end of the war, OSS engineers and technicians had formed a collection of labs, workshops, and experts that occasionally gave OSS a technological edge over its Axis foes.

|

|

An End and a Beginning

OSS trained many of the leaders and personnel who formed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Their ranks included four future Directors of Central Intelligence: Allen Dulles, Richard Helms, William Colby, and William Casey. Ironically, however, the one OSS veteran who did the most to promote such an agency—William J. Donovan—did not make the transition to it. He had led from the front, visiting his troops and surveying the ground in England, France, Italy, Burma, China, and even Russia. General Donovan was a charismatic leader and empire builder who inspired his people, but he was also a mediocre administrator, enamored of operations but bored by procedural detail. Tales of OSS inefficiency and waste—some of them true—delighted Donovan's critics. He had tirelessly battled bureaucratic rivals in Washington and London, but as the war drew to an end his enemies began to fear that he might actually win his campaign to create a peacetime intelligence service modeled on OSS. President Roosevelt made no promises, however, and after his death in April 1945, the incoming President, Harry S. Truman, felt no obligation to save OSS.

Victory in Europe in May 1945 allowed OSS to concentrate on Japan, but it also meant months of bureaucratic limbo for Washington headquarters. President Truman disliked Donovan. Truman mocked him in his diary, perhaps fearing that Donovan's proposed intelligence establishment might one day be used against Americans. The mood in Congress, moreover, was running against "war agencies" like OSS. Once the victory was won, the nation and Congress wanted demobilization—fast. This obstacle alone might have blocked a presidential attempt to preserve OSS or to create a permanent peacetime intelligence agency along the lines of General Donovan's plan.

Executive Order 9621 on 20 September dissolved OSS as of 1 October 1945, sending R&A to the Department of State and everything else to the War Department. Fortunately, Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy had saved the SI and X-2 Branches as the nucleus of a peacetime intelligence service. Within two years the President and the Congress found a new home for the personnel and assets saved in SSU under Col. William W. Quinn. They went to a new organization called the Central Intelligence Group (CIG) until the National Security Act of 1947 turned CIG into the Central Intelligence Agency, to perform many of the missions that General Donovan had advocated for his proposed peacetime intelligence service. Although CIA differed from OSS in important ways (which is why Truman endorsed it and not OSS), Donovan and his office deserve credit as forefathers of the Agency. Without Donovan's tireless advocacy of a modern intelligence service—and the record built by OSS during the war—the Truman administration would have taken longer to create the new intelligence establishment that the President wanted and might not have done this task as well.