The Olympic Games were a series of athletic competitions held for representatives of various city-states of Ancient Greece held in honor of Zeus.

The exact origins of the Games are shrouded in myth and legend but records indicate that they began in 776 BC in Olympia in Greece. They were celebrated until 393 AD when they were suppressed by Theodosius I as part of the campaign to impose Christianity as a state religion. The Games were usually held every four years, or olympiad, as the unit of time came to be known. During a celebration of the Games, an Olympic Truce was enacted so that athletes could travel from their countries to the Games in safety. The prizes for the victors were olive wreaths or crowns.

The Games became a political tool used by city-states to assert dominance over their rivals. Politicians would announce political alliances at the Games, and in times of war, priests would offer sacrifices to the gods for victory. The Games were also used to help spread Hellenistic culture throughout the Mediterranean. The Olympics also featured religious celebrations and artistic competitions. A great statue of Zeus, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world was erected in Olympia to preside over the Games. Sculptors and poets would congregate each olympiad to display their works of art to would-be patrons.

The ancient Olympics were rather different from the modern Games. There were fewer events, and only free men who spoke Greek could compete. As long as they met the entrance criteria, athletes from any country or city-state were allowed to participate. The Games were always held at Olympia rather than alternating to different locations as is the tradition with the modern Olympic Games. There is one major commonality between the ancient and modern Games, the victorious athletes are honored, feted, and praised. Their deeds were heralded and chronicled so that future generations could appreciate their accomplishments.

To the Greeks it was important to root the Olympic Games in mythology. During the time of the ancient Games their origins were attributed to the gods, and competing legends persisted as to who actually was responsible for the Games' genesis. These origin traditions and myths have become nearly impossible to untangle, yet a chronology and patterns have arisen that help people understand the story behind the Games.

History

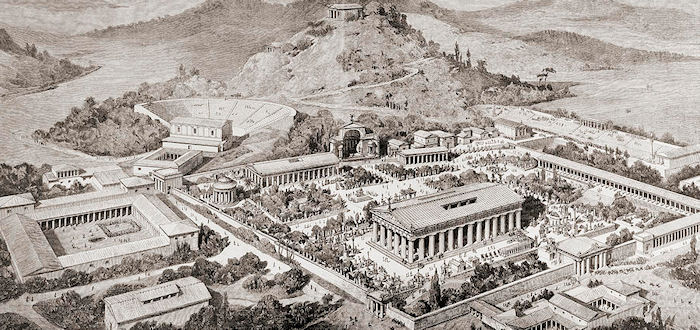

The games were held to be one of the two central rituals in Ancient Greece, the other being the much older religious festival, the Eleusinian Mysteries. The games started in Olympia, Greece, in a sanctuary site for the Greek deities near the towns of Elis and Pisa (both in Elis on the peninsula of Peloponnesos). The first Games began as an annual foot race of young women in competition for the position of the priestess for the goddess, Hera and a second race was instituted for a consort for the priestess who would participate in the religious traditions at the temple.

Being the consort of Hera in Classical Greek mythology, Zeus was the father of the deities in the pantheon of that era. The Sanctuary of Zeus in Olympia housed a 13-metre-high statue in ivory and gold of Zeus that had been sculpted by Phidias circa 445 BC. This statue was one of the ancient Seven Wonders of the World. By the time of the Classical Greek culture, in the fifth and fourth centuries BC, the games were restricted to male participants.

The historian Ephorus, who lived in the fourth century BC, is believed to have established the use of Olympiads to count years. The Olympic Games were held at four-year intervals, and later, the Greek method of counting the years even referred to these Games, using the term Olympiad for the period between two Games. Previously, every Greek state used its own dating system, something that continued for local events, which led to confusion when trying to determine dates. For example, Diodorus states that there was a solar eclipse in the third year of the 113th Olympiad, which must be the eclipse of 316 BC. This gives a date of (mid-summer) 786 BC for the first year of the first Olympiad. Nevertheless, there is disagreement among scholars as to when the Games began.

|

The Olympic Games were part of the Panhellenic Games, four separate games held at two- or four-year intervals, but arranged so that there was at least one set of games every year. The Olympic Games were more important and more prestigious than the Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian Games.

Finally, the Olympic Games were suppressed, either by Theodosius I in AD 393 or his grandson Theodosius II in AD 435, as part of the campaign to impose Christianity as a state religion. The site of Olympia remained until an earthquake destroyed it in the sixth century AD.

Culture

The ancient Olympics were as much a religious festival as an athletic event. The Games were held in honor of the Greek god Zeus. On the middle day of the Games 100 oxen would be sacrificed to Zeus. Over time Olympia, site of the Games, became a central spot for the worship of head of the Greek pantheon and a temple, built by the Greek architect Libon was erected on the mountaintop. The temple was one of the largest Doric temples in Greece. The sculptor Pheidias created a statue of the god made of gold and ivory. It stood 42 feet (13 m) tall. It was placed on a throne in the temple. The statue became one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. As the historian Strabo put it,

"...the glory of the temple persisted...on account both of the festal assembly and of the Olympian Games, in which the prize was a crown and which were regarded as sacred, the greatest games in the world. The temple was adorned by its numerous offerings, which were dedicated there from all parts of Greece."

Artistic expression was a major part of the Games. Sculptors, poets and other artisens would come to the Games to display their works in what became an artistic competition. Sculptors created works like Myron's Diskobolos or Discus Thrower. Their aim was to highlight natural human movement and the shape of muscles and the body. Poets would be commissioned to write prose in honor of the Olympic victors. These poems, known as Epinicians, were passed on from generation to generation and many of them have lasted far longer than any other honor made for the same purpose. Baron Pierre de Coubertin, one of the founders of the modern Olympic Games, wanted to fully imitate the ancient Olympics in every way. Included in his vision was to feature an artistic competition modeled on the ancient Olympics and held every four years, during the celebration of the Olympic Games. His desire came to fruition at the Olympics held in London in 1908.

Politics

Power in ancient Greece became centered around the city-state in the 8th century BC. The city-state was a population center that became organized into a self-contained political entity. These city-states often lived in close proximity to each other, which created competition for limited resources. Though conflict between the city-states was ubiquitous, it was also in their self-interest to engage in trade, military alliances and cultural interaction. The city-states had a dichotomous relationship with each other, on one hand they relied on their neighbors for political and military alliances, on the other they competed fiercely with those same neighbors for the resources necessary to sustain life. The Olympic Games were established in this political context. Representatives of the city-states would compete against each other at the Games.

In the first two centuries of the Games' existence Olympia had only regional religious importance. Greeks beyond the area immediately around the mountain did not compete in these early Games. This is evidenced by the dominance of Peloponnesian athletes in the victors' rolls. The spread of Greek colonies in the 5th and 6th century BC is repeatedly linked to successful Olympic athletes. For example, Pausanias recounts that Cyrene was founded c. 630 BC by settlers from Thera with Spartan support. The support Sparta gave was primarily the loan of three-time Olympic champion Chionis. The draw of settling with an Olympic champion helped to populate the colonies and maintain cultural and political ties with the city-states in proximity to Olympia. Thus Hellenistic culture and the Games spread while the primacy of Olympia persisted.

The Games faced a serious challenge during the Peloponnesian War, which primarily pitted Athens against Sparta, but in reality touched nearly every Hellenistic city-state. The Olympics were used during this time to announce alliances and offer sacrifices to the gods for victory.

During the Olympic Games, a truce, or ekecheiria was observed. Three runners, known as spondophoroi were sent from Elis to the participant cities at each set of games to announce the beginning of the truce. During this period, armies were forbidden from entering Olympia, wars were suspended, and legal disputes and the use of the death penalty were forbidden. The truce was primarily designed to allow athletes and visitors to travel safely to the Games and was, for the most part, observed. Thucydides wrote of a situation when the Spartans were forbidden from attending the Games, and the violators of the truce were fined 2,000 minae for assaulting the city of Lepreum during the period of the ekecheiria. The Spartans disputed the fine and claimed that the truce had not yet taken hold.

While a marshal truce was observed by all participating city-states, no such reprieve from conflict existed in the political arena. The Olympic Games evolved the most influential athletic and cultural stage in ancient Greece, and arguably in the ancient world. As such the Games became a vehicle for city-states to promote themselves. The result was political intrigue and controversy. For example, Pausanias, a Greek historian, explains the situation of the athlete Sotades,

"Sotades at the ninety-ninth Festival was victorious in the long race and proclaimed a Cretan, as in fact he was. But at the next Festival he made himself an Ephesian, being bribed to do so by the Ephesian people. For this act he was banished by the Cretans."

This situation repeated itself at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. In what is becoming a growing trend, many athletes are switching citizenships in order to compete at the Games. There are an equal number of countries willing to grant citizenship and monetary considerations to these athletes in exchange for their representation and the honor that comes with potential Olympic success. In this the Olympics have changed very little from their roots in antiquity.

Events

Only free men who spoke Greek were allowed to participate in the Ancient Games of classical times. They were to some extent "international", though, in the sense that they included athletes from the various Greek city-states. Additionally, participants eventually came from Greek colonies as well, extending the range of the games to far shores of the Mediterranean and of the Black Sea. To be in the Games, the athletes had to qualify and have their names written in the lists. Before being able to participate, every participant had to take an oath in front of the statue of Zeus, saying that he had been in training for ten months.

|

At first, the Olympic Games lasted only one day, but eventually grew to five days. The Olympic Games originally contained one event: the stadion (or "stade") race, a short sprint measuring between 180 and 240 metres, or the length of the stadium. The length of the race is uncertain, since tracks found at archeological sites, as well as literary evidence, provide conflicting measurements. Runners had to pass five stakes that divided the lanes: one stake at the start, another at the finish, and three stakes in between.

The diaulos, or two-stade race, was introduced in 724 BC, during the 14th Olympic games. The race was a single lap of the stadium, approximately 400 metres, and scholars debate whether or not the runners had individual "turning" posts for the return leg of the race, or whether all the runners approached a common post, turned, and then raced back to the starting line.

A third foot race, the dolichos, was introduced in 720 BC. Accounts of the race present conflicting evidence as to the length of the dolichos; however, the length of the race was 18-24 laps, or about three miles (5 km). The event was run similarly to modern marathons—the runners would begin and end their event in the stadium proper, but the race course would wind its way through the Olympic grounds. The course often would flank important shrines and statues in the sanctuary, passing by the Nike statue by the temple of Zeus before returning to the stadium.

The last running event added to the Olympic program was the hoplitodromos, or "Hoplite race", introduced in 520 BC and traditionally run as the last race of the Olympic Games. The runners would run either a single or double diaulos (approximately 400 or 800 yards) in full or partial armour, carrying a shield and additionally equipped either with greaves or a helmet. As the armour weighed between 50 and 60 lb (27 kg), the hoplitodromos emulated the speed and stamina needed for warfare. Due to the weight of the armour, it was easy for runners to drop their shields or trip over fallen competitors. In a vase painting depicting the event, some runners are shown leaping over fallen shields. The course they used for these runs were made out of clay, with sand over the clay.

|

Over the years, more events were added: boxing (pygme/pygmachia), wrestling (pale), a very bloody pankration (regulated full-contact fighting, similar to today's mixed martial arts), chariot racing, and several other running events (the diaulos, hippios, dolichos, and hoplitodromos), as well as a pentathlon, consisting of wrestling, stadion, long jump, javelin throw, and discus throw (the latter three were not separate events).

The winner of an Olympic event was awarded an olive branch and often was received with much honour throughout Greece, especially in his home town, where he was often granted large sums of money (in Athens, 500 drachma, a small fortune) and prizes including vats of olive oil. Sculptors would create statues of Olympic victors, and poets would sing odes in their praise for money.

The athletes usually competed naked, not only as the weather was appropriate, but also as the festival was meant to celebrate, in part, the achievements of the human body. Olive oil was occasionally used by the competitors, not only to keep skin smooth, but also to provide an appealing look for the participants.

Revival

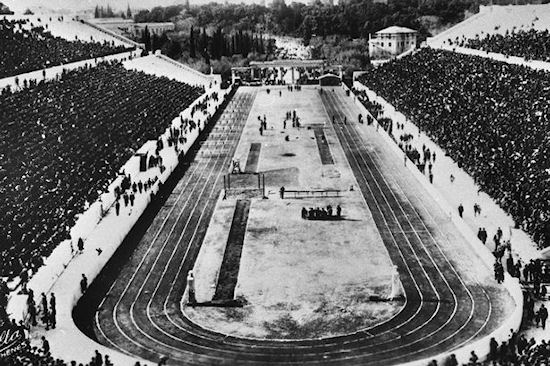

Greek interest in reviving the Olympic Games began with the Greek War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1821. It was first proposed by poet and newspaper editor Panagiotis Soutsos in his poem "Dialogue of the Dead", published in 1833. Evangelis Zappas, a wealthy Greek philanthropist, sponsored the first Olympic Games in 1859, which was held in an Athens city square. Athletes participated from Greece and the Ottoman Empire. Zappas funded the restoration of the ancient Panathenaic stadium so that it could host all future Olympic Games. In 1866, a national Olympic Games in Great Britain was organized by Dr. William Penny Brookes at London's Crystal Palace.

The Panathinaiko Stadium hosted Olympics in 1870 and 1875. Thirty thousand spectators crowded in to and around the stadium in 1870 - bigger than almost any crowd at Coubertin's IOC Olympics from 1900 to 1920.

In 1890, after attending the Olympian Games of the Wenlock Olympian Society Baron Pierre de Coubertin was inspired to found the International Olympic Committee. Coubertin built on the ideas and work of Brookes and Zappas with the aim of establishing internationally rotating Olympic Games that would occur every four years. He presented these ideas during the first Olympic Congress of the newly created International Olympic Committee (IOC). This meeting was held from June 16 to June 23, 1894, at the Sorbonne University in Paris. On the last day of the Congress, it was decided that the first Olympic Games, to come under the auspices of the IOC, would take place two years later in Athens. The IOC elected the Greek writer Demetrius Vikelas as its first president.

|

The first Games held under the auspices of the IOC was hosted in the Panathenaic stadium in Athens in 1896. These Games brought 14 nations and 241 athletes who competed in 43 events. Zappas and his cousin Konstantinos Zappas had left the Greek government a trust to fund future Olympic Games. This trust was used to help finance the 1896 Games. George Averoff contributed generously for the refurbishment of the stadium in preparation for the Games. The Greek government also provided funding, which was expected to be recouped through the future sale of tickets to the Games and from the sale of the first Olympic commemorative stamp set.

The Greek officials and public were enthusiastic about the experience of hosting these Games. This feeling was shared by many of the athletes, who even demanded that Athens be the host of the Olympic Games on a permanent basis. The IOC did not approve this request. The committee planned that the modern Olympics would rotate internationally. And so began the story of the modern Olympic Games.