On the eve of 1959, the US-backed Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, instead of welcoming in what might have been his 25th year in power, spent the evening hurriedly packing his bags and preparing to flee to the Dominican Republic.

A guerrilla army of no more than 2,000 fighters had effectively routed his government's security forces and looked set to take control of the country.

The collapse of Batista's regime, which had effectively ruled Cuba since 1934, sent shock waves around the world. It marked the end not only of a repressive dictatorship, but also over 60 years of US political and economic domination of the island. And it provided a powerful example to those struggling against imperialism elsewhere, particularly in the rest of Latin America, that US imperialism was not invincible, and that revolutions could succeed in relatively underdeveloped countries.

Imperialist domination

Foreign domination of Cuba began in 1511 when the Spanish first colonised the island. They ruled until their expulsion in 1898 following a three-year war. Far from achieving independence though, the war in reality transferred power from Spain to the US, with Washington appointing most high-ranking officials and even inserting a clause in the new Cuban constitution guaranteeing the US the right to intervene militarily whenever deemed necessary. US corporations dominated the economy, controlling 60 per cent of agricultural land, most of which was used for sugar growing, and much of Cuban industry.

A revolt in 1933 overthrew the pro-US government of Gerardo Machado and brought to power a new regime which immediately rescinded the pro-US clauses in the Cuban Constitution, nationalised the electricity industry and introduced shorter working hours. Within months however this new government was in turn deposed by a military revolt led by army sergeant Fulgencio Batista, whose right-wing politics won him the tacit backing of the US.

US domination was thereby secured. By the 1950s, 70 per cent of imports and exports were controlled by US interests and 1.2 million hectares of land was owned by US corporations. The reliance of the Cuban economy on sugar exports was exploited by the US to prevent economic development in areas that might pose a threat to US producers. The tourism industry, employing at the time 20 per cent of the Cuban workforce, catered almost exclusively to Americans looking for cheap rum and prostitution. Corruption in the US-controlled state bureaucracy was rife.

As a result, the Batista regime enjoyed very little support within Cuba outside of the immediate beneficiaries of its corrupt practices.

Opposition

Opposition to the government overwhelmingly took the form of populist nationalism, drawing its support largely from unemployed and impoverished peasants in the countryside and sections of the middle class in urban areas. Middle-class students, frustrated with the lack of opportunities and rampant corruption of the government, were a particularly important component of the opposition.

The left, which could have posed an alternative to the prevailing nationalist politics based on class struggle and the working class, was dominated by the Communist Party. Rather than pose any alternative however, the communists instead discredited themselves through striking deals with Batista to secure their control over some trade unions and a stake in the government in return for supporting the regime. This meant the populist nationalists faced very little competition from the left in their efforts to mount a challenge to Batista.

Resistance

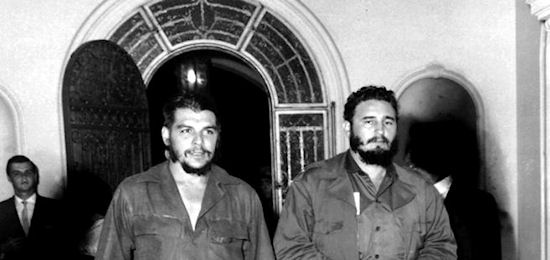

In 1953 an attack was organised on the Moncada barracks, led by the law graduate son of wealthy land owners, Fidel Castro. The attack was unsuccessful and many of those involved were captured and imprisoned. Nevertheless, the determination they demonstrated earned the fighters much admiration and established them as the leaders of a new struggle for national independence. "The 26th July Movement", as Castro's guerrillas came to be known, was a reference to the Moncado attack.

Upon his release from jail in 1956, Castro undertook to organise a guerrilla army with the aim of militarily defeating the Batista regime. Following their disastrous arrival in Cuba by boat, in which several of Castro's followers were killed, the nucleus of this new army took to the mountains and set about building their forces.

Confrontation with the government escalated in 1958. Following an announcement in March by Batista that the election scheduled for June would be postponed, an offensive was launched involving military attacks and a general strike. The strike failed to involve significant numbers of workers, crucially in the capital Havana, due partly to the movement's lack of influence within the working class and partly to the indifference to the strike on the part of the traditional union leaders. The debacle added weight to the argument advanced by Castro that the military struggle should take precedence over all other forms of resistance.

Militarily, the guerrilla campaign was able to hold its own and eventually force the government to retreat, despite Batista's far superior fire-power and numbers. Enjoying no significant support within Cuba, Batista was also beginning to fall out of favour with the US. The elections, eventually held in November, highlighted the political isolation of the government, with a voter turnout of less than 30 per cent in most areas. As declining morale amongst the troops gave way to more guerrilla victories, and as the rebels advanced steadily on the capital, the government collapsed.

Castro in power

Castro emerged as the undisputed leader of post-revolutionary Cuba. His new government promptly carried through land reforms, nationalising all land controlled by large estates, both US and Cuban, and nationalised the US-owned telephone and electricity companies. They also accepted aid from Russia, the US's Cold War rival, in the form of oil imports.

|

These moves were not well received in Washington. The US government immediately threatened to cut Cuban sugar imports, withdrew US capital and began preparing for an invasion of the island.

It was in this context that the revolution came to be seen as "communist". Castro declared Cuba a socialist state and merged the 26th July Movement with the Communist Party in 1961, despite his lack of interest in or sympathy for class politics or communism prior to or during the revolution.

There was a logic to this apparent transformation. Castro recognised in the Russian model of "communism", with its state-run and centrally planned economy, his vision of a strong state being the means through which the Cuban economy could be modernised and achieve some independence. And insofar as his government implemented the program of the July 26th Movement, Castro was brought into conflict with US interests. This meant another major trading partner was needed, and in the context of the Cold War, this involved making an alliance with Russia and the economic bloc it presided over.

It is important to see that neither Russia nor Cuba had anything to do with genuine communism or socialism, despite the rhetoric. Socialism, as Marx insisted, involves the self-conscious liberation of the working class. It cannot be brought about through change introduced from above, and it is not achieved simply through state control. Only workers themselves, by taking control of their workplaces and forming new organisations and structures to run production democratically, can create a society that is genuinely equal and controlled by the majority.

Castro's adoption of a new title to describe it therefore did nothing to change the nature of the revolution he led. It was always about establishing a stronger and more independent form of Cuban capitalism rather than a society run by workers. This involved unity on a nationalist basis, not a class basis. As Castro told a crowd in New York's Central Park in April 1959, "Victory was only possible because we united Cubans of all classes and all sectors around a single, shared aspiration."

The goal of those leading the revolution was not to establish a society free from exploitation and class divisions, but one more economically independent of the US in which they could have a substantial stake.

The working class, while enthusiastically supporting the ousting of Batista, played a minor role in events. Not because they were conservative or poorly organised – workers in Cuba were traditionally well-unionised (around 50 per cent were members of unions in the 1950s), and were largely opposed to Batista. Rather it was because many of the nationalist leaders were hostile or indifferent to the organised working class. In part this was because they saw armed struggle as more important than industrial action and in part because the union leadership, dominated as it was by the both corruption and the class collaborationist politics of the Communist Party, were seen as politically conservative.

For the union leadership, working class action was more often than not a threat to their economic position and the future stability of Cuban capitalism. Without revolutionary leadership or organisation then, the working class therefore offered only passive support for the revolution.

While the Cuban revolution was not socialist, it nevertheless represents an important victory in the struggle against imperialism. But in the struggle to free humanity, not just from imperialist domination but also from the profit-centred priorities of the capitalist system which condemn people to poverty and misery every day, it is an inadequate model to emulate. The struggle for socialism, for a world without class divisions, must be based on the power workers have over production and profit-making.